In general, you’d expect goods and services that don’t change over time in terms of their cost to produce or provide would only increase in price with general inflation. A Coca-Cola cost more than it did 40 years ago, but in real dollars adjusted for inflation, it’s about the very same base price. A 1980 Toyota Corolla in 1980 costs about the same in real dollars as the 2020 Toyota Corolla. The cost to manufacture these products, and overhead expenses, and distribution is all about the same.

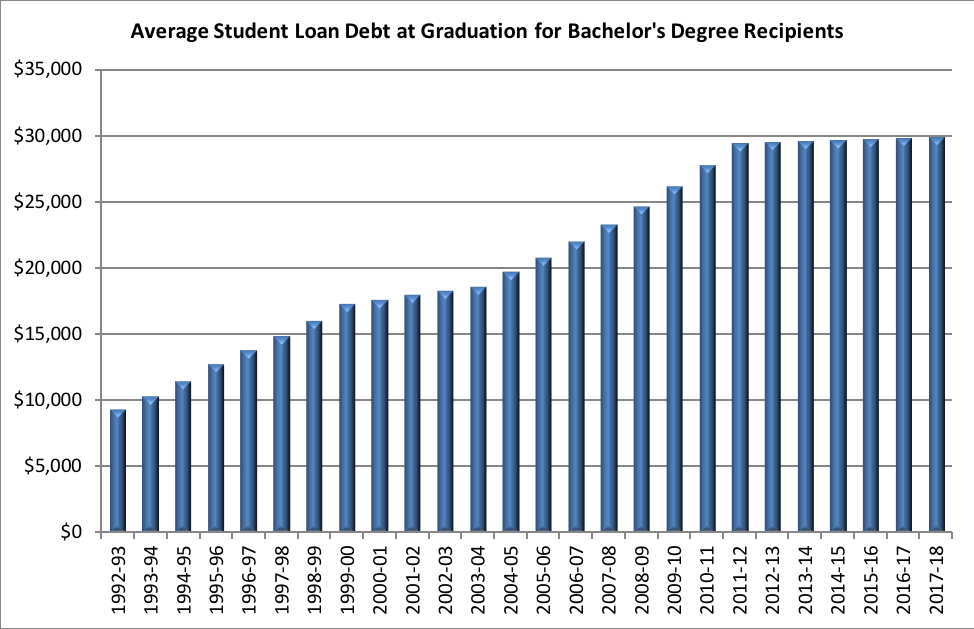

Which leads to the cost of college. Up until the 1980’s, the cost of tuition was in line with the rise in inflation. Then, no longer. The cost since the mid-80’s has outpaced inflation by 250%. That’s not a small difference. That’s a huge difference. If we applied that price to the Toyota Corolla, that economical sedan would cost you $45,000 today, rather than around $19,000 out the door.

There are many theories behind the remarkable rise in the average cost of attending college in the last several decades. And they are largely theories as nobody particularly trusts the colleges and universities to honestly state the full and detailed reasons why.

Those institutions point to their increased cost structures, what with technology upgrades for the digital age, demands for improved housing and dining options (which don’t affect tuition costs), and increased labor costs across the boards. Additionally, colleges note, accurately, that with the sheer rise in the number of incoming students, the per capita amount states provide in support for lower income students has continued to drop over the years.

Many colleges have increased their numbers of low-income students receiving financial assistance, percentage wise, which does put pressure on the listed price or the price paid by those not on financial assistance to pay to compensate to cover the entire class costs. But, schools that have not been quite as ambitious in raising their financial-aid student percentages still have increased their college costs in line with their competitors. Which leads one to believe many schools are raising prices whether or not their average student net payments are changing or not.

While these many reasons provided by the colleges and universities may be accurate to some degree, we’re still left with the Coke and the Corolla analogy. That is, a college degree is still however many classes and courses as it’s always been, classrooms are still classrooms, dorms are still dorms, and professors will tell you they aren’t making some new untold fortunes. Which leads to two more likely drivers of the much higher costs to attend college.

Supply and Demand

We’ve discussed the dramatic uptick in college enrollment in the last several decades. Most notably from female high school graduates, whose participation in college has risen dramatically since 1970. There are four million high school students graduating in the U.S. now each year. And two-thirds of them are attending college. That’s a much larger number than but a few decades ago. At the same time, there are not that many new brick and mortar colleges to attend.

While schools are expanding enrollment class sizes and facilities to handle more students, college has become a seller’s market in the United States. If you’ve studied basic economics, you know that if there are twice as many people trying to buy the same thing as there used to be, demand has doubled for that product. Invariably that means higher prices. If you live in a neighborhood that has become a hot option for new home buyers, you’ve experienced this phenomenon first hand. Much higher home sale prices. Most especially if there are no empty spaces to build new homes in the same area.

International Students

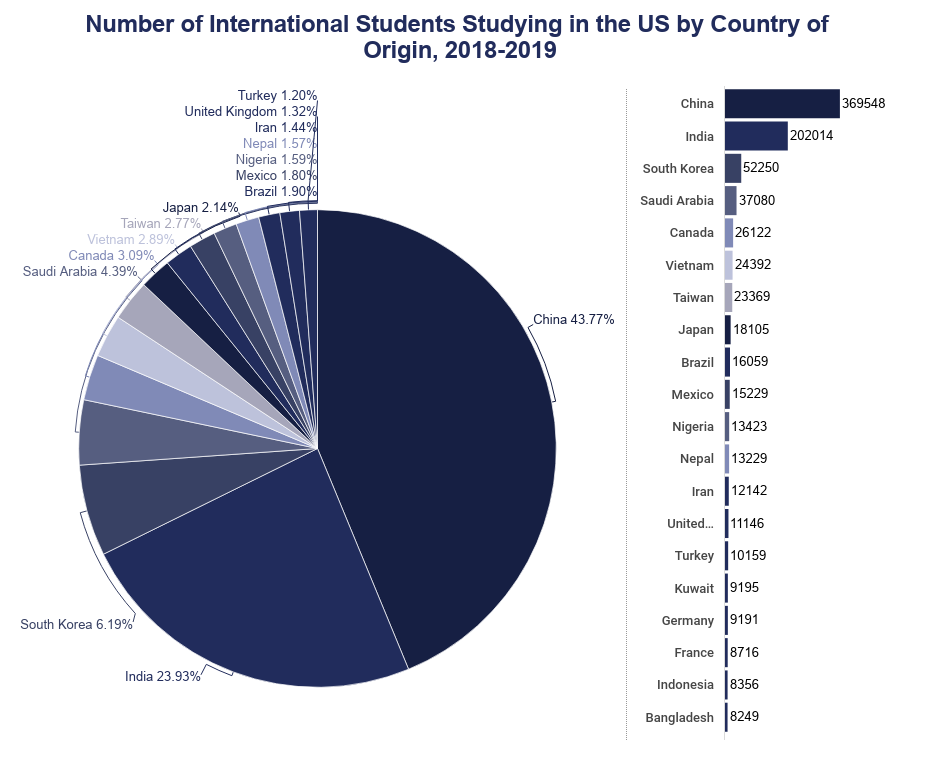

Adding to the increased demand side for college attendance is the dramatic rise in International Students attending American universities. There are now over a million International students, largely from China and India, attending U.S. institutions. While the majority are here for graduate study, more than 400,000 annually enroll as undergraduate students.

International students provide private institutions with full tuition payments or for public institutions, full out-of-state pricing structures. In fact, many graduate programs charge additional costs for international students, meaning that they are paying more than anybody else at the university to attend.

While the total college population of international students in the U.S. is 5.1%, that number can rise substantially higher at reputable institutions that encourage international student enrollment. As an example, undergraduate enrollment at UCLA is 12% International while graduate enrollment is 20% International.

Public outcry has risen over the ever-increasing number of international students at these public universities compared to In-State student spots, but the universities insist that the funds provided by these foreign students allow them to keep their public tuition costs controlled. Though that claim is certainly in the eye of the beholder.

Student Loans

Throughout most of our nation’s history, college was not a path subsidized or supported generally by the Federal government. Most people didn’t attend. Those that did tended to come from more financially sound families or they were able to secure private loans for the cost. 100 years ago, less than 4% of people in the United States had a four year college degree. Now it’s 35%, and that includes both men and women. When you add in two year degrees, that number increases even further.

Beginning in the 1970’s, the Federal government became a big player in college financing. While Pell grants and similarly styled grants for the impoverished existed, this was the moment when the U.S. government got full force behind a broad plan to provide funding for college education to the middle class. This began the rise of the college student loan. Very easy to qualify, very easy to obtain, very low deferred interested rates — but now, the bane of many Millennial’s existence.

Student loans subsidized the cost of college for many students and dramatically opened up the college opportunity for students from backgrounds who might otherwise have found it unaffordable. That was the goal. However, perhaps the unintended consequence was now everybody had funds for college. That meant more people going to college who perhaps were not necessarily driven internally to do so, but also that colleges now could start charging more money.

Back to basic economics. The price of any good is the highest price a seller can convince a buyer to pay. Imagine everywhere is a car dealership. It’s a haggle, whether overtly or intrinsically. When the shoppers have more money, they can afford to pay higher prices, and with a product in demand like a college education, they will. Hence, the schools raise the prices to capture those extra dollars. The Federal Student Loan program gives money to high school graduates and the schools say, thank you very much, you can now pay us more.

The colleges will not admit this practice openly. But then they can’t explain why their list prices are rising so dramatically faster than all other goods in the consumer market, save for healthcare (which naturally is also subsidized heavily by government payment).

The Net Result — College Is Crazy Expensive

No matter the reason, the price to attend college is skyrocketing. That is especially so for private institutions where top schools are now charging upwards of $70,000 a year for tuition, room, and board. But also public universities where while not nearly as expensive due to public funding support, also continue to increase everywhere and in a signifiant manner.

Until the demand side changes, or the Federal aid side, there’s no reason to expect this hockey stick rise to curtail. Some schools like USC are now declaring that low income students will receive even greater or near total support for the tuition cost to attend school. However, these remain a small percentage of overall students and only add to the costs charged to the majority.

When you combine the rising cost of college with the reduced job and salary landscape for graduates, you can see why college loan debt is in meteoric and devastating conditions across the country.