Go to college. Get a good job. Do better than your parents. That was the mantra when it was true. That remains the mantra, even though it’s no longer true for so many. Is anybody looking at the numbers? They should.

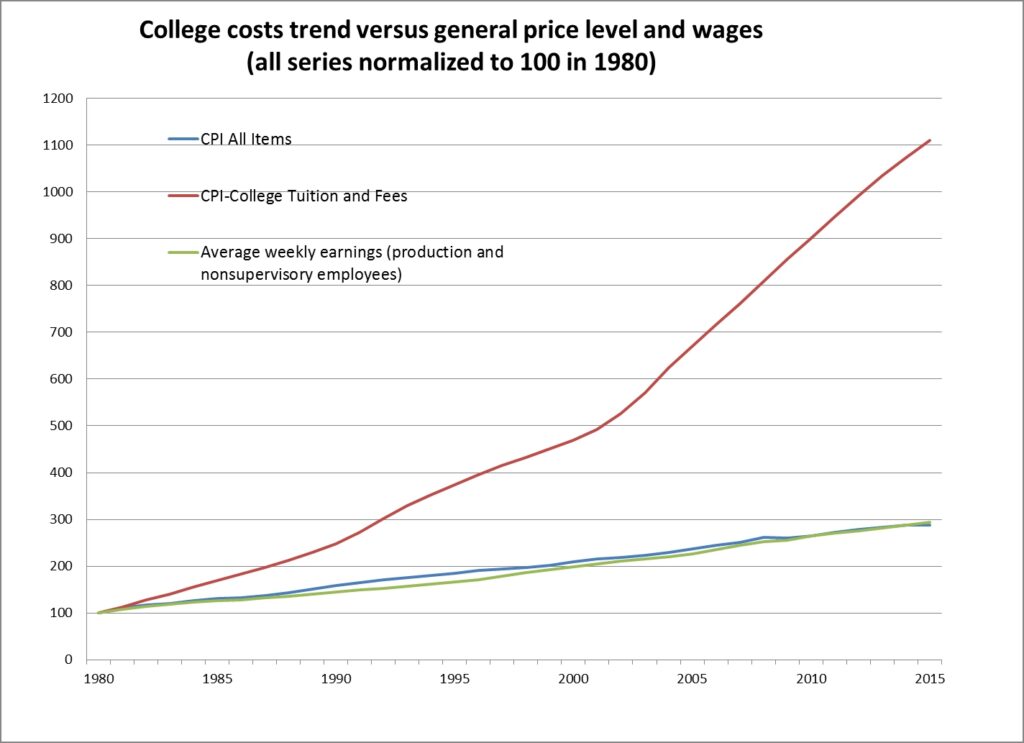

We know that the cost of attending college in real dollars has increased dramatically in the past several decades. There are many reasons cited for this rapid rise in post-secondary school cost; most notably among them the easy access to college loans. As more students from modest income backgrounds now had access to money for college, the schools themselves began to raise their prices to capture that new spending power.

As the price of both public and private colleges has risen, the job and financial prospects for college graduates have continued to decline. This new reality is whispered about in hushed voices as if it’s heretical to say aloud. The results of this new reality are hitting the U.S. economically and socially in a rather dramatic fashion. Our nation is experiencing huge discontent among recent college graduates who find themselves living at home with more college debt notices than responses to job applications.

Naturally, college is not merely a financial investment. There are many intangible benefits associated with the college experience. For one, advanced education, often in a variety of subject matters that simply were not available in your standard K-12 education. Doubtful your high school had a French Lit class. Or Gender Studies. Or a Chinese dissident teaching a seminar on agrarian policies under Mao. Colleges offer a unique social experience, a variety of extracurriculars, sports, arts, and other collegiate events and areas of interest you can’t really find off campus. Certainly not all at your doorstep.

We’re considering none of that in this case. That’s a subjective consumption value. We’re looking at simply the economic proposition of college. Because nobody else does. And it’s incredibly important.

Case Study: UNLV

The University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) is a typical, medium-sized state school. Its student population is highly diverse — racially, culturally, and financially. The in-state cost to attend school is well within the average range across the country for public universities.

The cost to attend UNLV for tuition, room, and board for Nevada residents is about $23,000 a year. This is in contrast to full-tuition private schools like USC where that number has grown closer to $70,000 per year. UNLV is an affordable option in pursuit of a bachelor’s degree.

In assessing the cost to attain a bachelor’s degree, you might think, multiply that annual cost by four years of college. That’s traditionally how you see “cost of college” examples. But, not so fast. According to CollegeFactual.com, only 13% of full-time UNLV students graduate in four years. (UNLV claims that number is now actually closer to 19%). That’s shockingly low to most people not familiar with college matriculation numbers these days. The six-year graduation rate at UNLV according to CollegeResults.org is 41%. (UNLV claims it’s currently 44%.). Less than half the full-time students at UNLV end up graduating, and for those who do graduate, very few do so in four years.

At 13% or even 19%, UNLV is below the national average in its 4-year graduation rate. Still, the nationwide 4-year graduation rate average for public universities hovers around a rather dismal 33%. And the nationwide 6-year average around 45%. Less than half the kids who start bachelor’s degrees at public colleges and universities even graduate. And even for those who do, four years is no longer the right metric. Five years is the new minimum for most. Six years is becoming more common.

At private colleges and universities, the graduation numbers are better, but still surprisingly low. 53% of full-time students are graduating in 4-years from these schools, 65% in six years. And while better than the public colleges, private schools on average are far more expensive, often easily double, so extra years there (let alone wasted years there) are especially financially painful.

Risk-Adjusted Cost Matters

To assess the current cost of college in 2020, you ought to multiply the annual cost by more than four, and additionally, consider the risk-adjusted cost.

If half or more of the students starting your college aren’t receiving a degree, then the real cost when adjusted for outcome risk is twice what you see on paper. If you make it through half of a degree at UNLV at $96,000, then never finish, that money is lost, economically at least. (There is some residual value to those college credits if you do change schools, though it’s not assumed a sizable percentage of people leaving school are taking those credits to other institutions to “cash-in” on their value. )

Risk adjusted cost matters. Would you buy a house if there was a 50% chance that in six years it would fall into a sinkhole? You’d probably ask the seller for a huge discount. Colleges don’t offer discounts for risk.

This ought to promote an honest discussion of who doesn’t complete college and why. In general, students from lower-income backgrounds drop out more. The reasons behind this are not simple, but much can be attributed to the relatively large financial burden to themselves and their families of attending college. On a more individual personality basis, students with a devotion to their college outcome and a generally higher commitment to putting in the work will dropout less than students who attend college without similar motivation.

Despite the popular chants, college is not for everybody. And when the fit is unaligned, the financial outcome tends to suffer as well.

Forget the Cost of College, It’s All About the J-O-B

Considering college as an investment, you have to ask, an investment toward what. Likely that’s a good job, a rewarding career, and the ability to take care of yourself and eventually a family.

However, according to a recent report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the unemployment rate for recent college graduates was higher than the general population. If you know people who graduated from college recently, you’re probably aware of the difficulty many have been having finding full-time jobs.

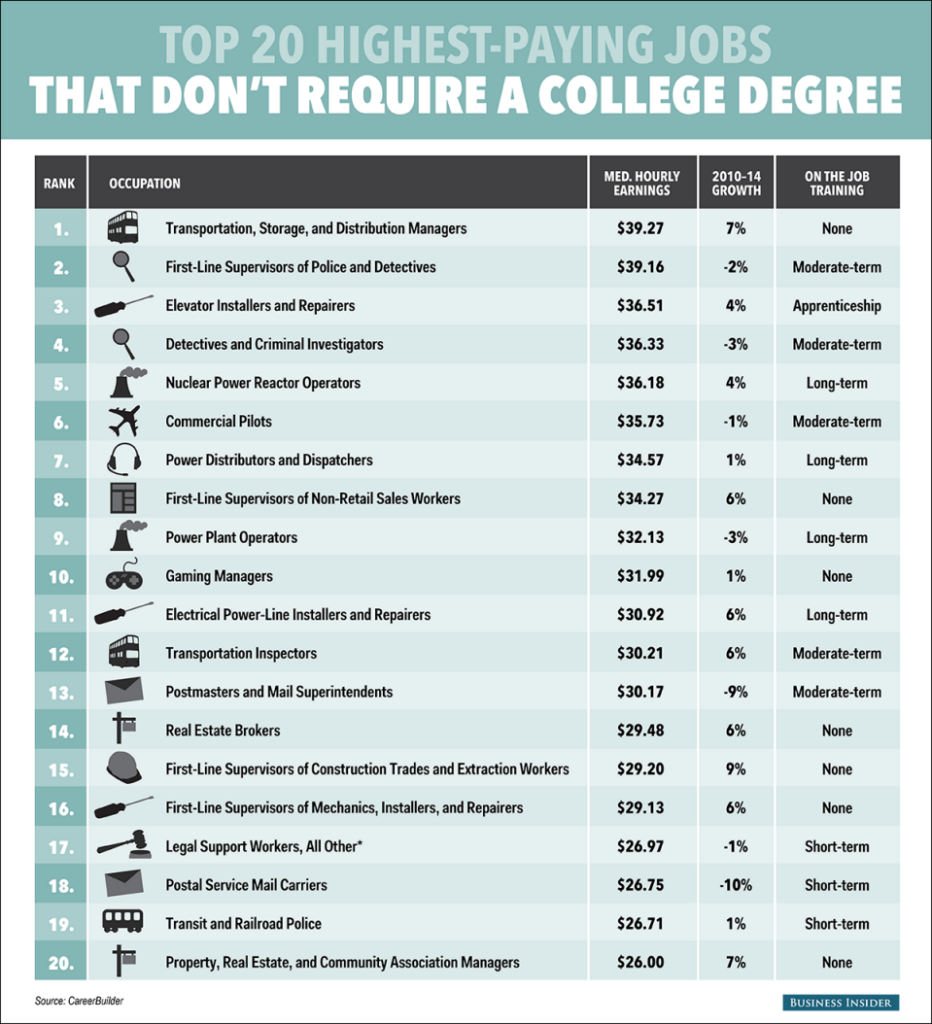

According to the same report, 41 percent of recent college graduates who are fortunate to have jobs are working in jobs that don’t require a college degree. These would be service jobs in retail, hospitality, clerical, and similar.

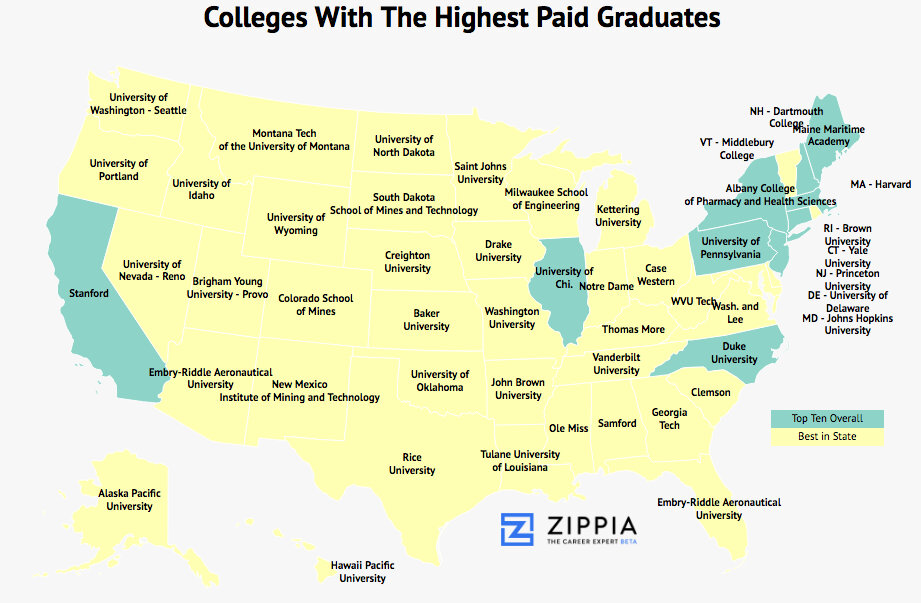

In this buyer’s market for employers, they can be more selective when hiring college graduates for professional positions. This heavily favors graduates from more preeminent, private institutions. While the national average finds 41 percent of recent college grads with jobs working in jobs that don’t require a college degree, UNLV and Stanford do not have the same percentage. It’s going to be far higher than the average for those graduates out of schools such as our example case, UNLV.

The evidence of this disparity is presented in the earnings differential post-college. A survey of students 10-years following college enrollment at UNLV found them earning an average of 45,000 a year, while the average Stanford graduate was earning $92,000.

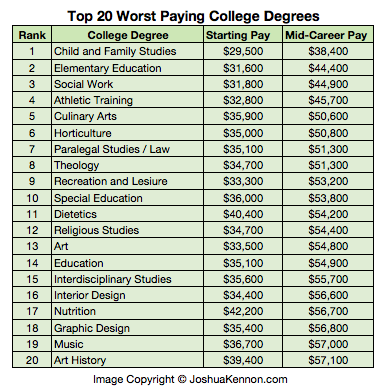

If you dig deeper into the area of college study, you will find the job prospects and earnings vary widely. Fields such as nursing, environmental science, engineering, and other technically focused educational tracts offer much higher levels of post-collegiate employment than the humanities and areas of general education. For the social sciences and the arts and general education, the prospects are particularly bleak.

So You’re Saying the Top Schools Are Still a Good Investment?

Yes. In general. The higher the ranking of the school, both for private and public colleges, the more it costs, the higher the graduation rates, and the higher the post-college earnings. We used Stanford earlier as an example. Pretty much everybody who starts at Stanford graduates with a bachelor’s degree. The ambitious nature of the incoming students, the high dollar commitment from the get-go, and the value to finishing provide a very high completion motivation factor.

Elite public schools follow a fairly similar pattern. Recently ranked the #1 public university in the country, UCLA has a far higher graduation rate (90% in six years) than other public universities, and the jobs and job incomes after graduation are rosier. And it still only costs half of what Stanford does.

However, for high school graduates who aren’t at or near the top in their high school classes, while also being amazing athletes or piano players or sons of foreign royalty, Stanford and UCLA aren’t viable options. For the vast majority of college students at the vast majority of colleges and universities, our sour financial return metrics do apply.

This Is Disheartening News About College as an Investment, No Way It Could Get Worse

Umm. Opportunity cost.

Anybody who’s taken a labor economics class probably remembers the teacher comparing the financial case of a high school dropout and a medical doctor. Assume the high school dropout leaves school at 16 and becomes a truck driver. While pay is low in the first several years, the work is abundant, and the raises are small but inevitable.

The kid at 16 is broke when he starts, owes nothing, but has nothing. It’s easy to track his or her economic value from their selected path. It’s their work income. And it starts at 16.

Meanwhile, the future doctor attends college, then four years of medical school, paying and/or borrowing to the tune of several hundred thousand dollars, all without any money coming in during that eight to nine-year time span. Following that, a residency where they are paid a fraction of their future salary for several more years (not to mention working 100-hour weeks).

By their early 30’s, the kid turned truck driver has been making money for a decade and a half without any expense, while the doctor finds him or herself at the same age worth a large negative number.

Finally, the doctor finally enters the “real doctor world” with real pay. While the doctor’s income is substantially greater than the truck driver’s pay, based on their very different financial starting points, it may take the doctor 10 years before their net balance equals that of the truck driver.

The point of the exercise — for about 25 years the high school dropout is doing financially better than the doctor. And if you look at the Net Present Value of the same exercise, where the doctor doesn’t make money for decades, the truck driver fares even better.

Now layer that exercise over the college financial equation. Not only are you paying to attend college for four or five or six years, but those are also years when you’re not making money. Maybe you have a part-time job or a school job that helps pay the bills, but it’s not close to full-time pay.

Say you’re working a full-time job, even minimum wage for the first year or two, for those same college years. California is moving soon to a $15 an hour minimum wage; Nevada only $11 by 2022 but with a much lower cost of living. Say, on average it’s $25,000 a year, and small raises each year thereafter. Four to six years of that, or most of that if you’re working part-time, is now being not earned if you got to college. In our UNLV model then, the cost to attend for 5 years is $115,000, but you’re also forgoing another well over $100,000 in wages from the job you weren’t working. Or $215,000 in actual net cost.

Now you see how even a very modestly priced in-state college like UNLV comes with a big expense. And with the graduation rates as they are, the job difficulties after college especially finding a college-degree required job that may pay more, the value proposition is pretty brutal.

A Final Word on The College Cost Equation

This is merely a financial breakdown of the college decision. There are reasons to attend college even if the financial investment is remarkably poor. Maybe you want to keep learning in the classroom. Maybe it’s a point of personal or family pride. Certainly, some career fields like our aforementioned doctor require you to attend college so there’s little choice.

But every indication is that the financial investment outcome for most people attending most colleges simply isn’t positive. That isn’t discussed nearly enough in our country even as it’s become a massive source of frustration, disappointment, and disheartenment for both students and parents alike.

Pew Research has found that a majority of 20-somethings in the U.S. are now living at home with their parents. For comparison’s sake, that’s higher than the same measure during the Great Depression. It’s the highest ever in U.S. history. Much of it has to do with crushing student debt combined with a lack of post-collegiate job opportunities with decent pay.

The investment question is not the only question that high school graduates and their families should be considering, but it is incredibly important. While easy access to college loans has made college a possibility for so many more graduating high school students, it’s also become a financial product itself. And the return on that product is never discussed.